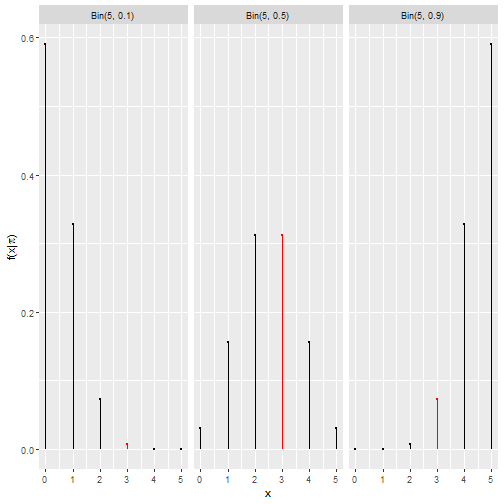

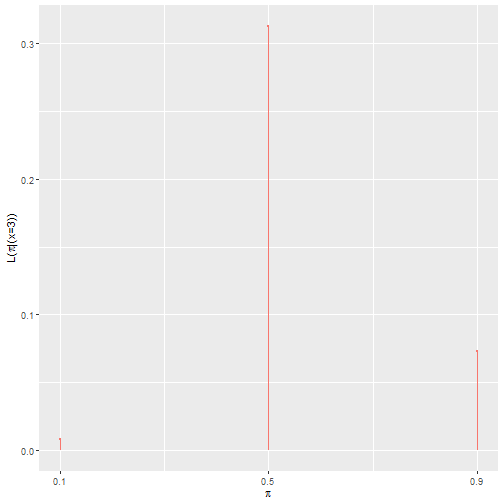

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Bayes’ Rule for Events and Discrete Random Variables ### Dr. Dogucu ### 2020-01-08 --- layout: true <div class="my-header"></div> <div class="my-footer"> Copyright © <a href="https://mdogucu.ics.uci.edu">Dr. Mine Dogucu</a>. All Rights Reserved.</div> --- ## Note on Copyright Even though the website by default says Copyright Dr. Mine Dogucu some of the materials presented in this lecture and the subsequent lectures are product of a collaboration with Drs. Alicia A. Johnson and Miles Ott. ## Announcements - Going over cat problem - All about you survey --- ## Spam email Priya, a data science student, notices that her college's email server is using a faulty spam filter. Taking matters into her own hands, Priya decides to build her own spam filter. As a first step, she manually examines all emails she received during the previous month and determines that 40\% of these were spam. --- ## Prior `\(P(S) = 0.40\)` If Priya was to act on this prior what should she do about incoming emails? --- ## A possible solution Since most email is non-spam, sort all emails into the inbox. This filter would certainly solve the problem of losing non-spam email in the spam folder, but at the cost of making a mess in Priya's inbox. --- ## Features of spam emails Priya observes the following about her latest incoming email. Which of the following is more likely to be a feature of a spam email? - The email was sent at 1:03am - The email was sent by an email address which started with the letter _p_. - The email came from outside the college. - The email was written in all capital letters ("all caps") and its subject line. --- ## Data Focusing on the last feature, Priya decides to look at some data. In her one-month email collection, 20% of spam but only 5% of non-spam emails used all caps. Write this information using probability notation. --- <div id="htmlwidget-acd4e5da11cee5f2350c" style="width:504px;height:504px;" class="grViz html-widget"></div> <script type="application/json" data-for="htmlwidget-acd4e5da11cee5f2350c">{"x":{"diagram":"\n digraph {\n # graph aesthetics\n graph [ranksep = 0.5]\n\n # node definitions with substituted label text\n 1 [label = \"Prior: \n Only 40% of emails are spam.\"]\n 2 [label = \"Data: \n All caps is more common among spam.\"]\n 3 [label = \"Posterior: \n Is the email spam or not?!\"]\n\n # edge definitions with the node IDs\n 1 -> 3\n 2 -> 3\n }\n","config":{"engine":"dot","options":null}},"evals":[],"jsHooks":[]}</script> --- Which of the following best describes your posterior understanding of whether the email is spam? a. The chance that this email is spam drops from 40% to 20%. After all, the subject line might indicate that the email was sent by an excited professor that's offering Priya an automatic "A" in their course! b. The chance that this email is spam jumps from 40% to roughly 70%. Though using all caps is more common among spam emails, let's not forget that only 40% of Priya's emails are spam. c. The chance that this email is spam jumps from 40% to roughly 95%. Given that so few non-spam emails use all caps, this email is almost certainly spam. --- # Calculating the posterior --- # From prior to posterior --- # Review: Discrete probability models Let `\(X\)` be a discrete random variable with probability mass function (pmf) `\(f(x)\)`. Then the pmf defines the probability of any given `\(x\)`, `\(f(x) = P(X = x)\)`, and has the following properties: `\(\sum_{\text{all } x} f(x) = 1\)` `\(0 \le f(x) \le 1\)` for all values of `\(x\)` in the range of `\(X\)` --- ## Notation - We will use _Greek letters_ (eg: `\(\pi, \beta, \mu\)`) to denote our primary variables of interest. - We will use _capital letters_ toward the end of the alphabet (eg: `\(X, Y, Z\)`) to denote random variables related to our data. - We denote an observed _outcome_ of `\(X\)` (a constant) using lower case `\(x\)`. --- ## PhD admissions Let X represent a random variable that represents the number of applicants admitted to a PhD program which has received applications from 5 prospective students. That is `\(\Omega_X = \{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}\)` We are interested in the parameter `\(\pi\)` which represents the probability of acceptance to this program. We know that `\(\pi\)` can be any value between 0 and 1 but for now we will only consider three possible values of `\(\pi\)` as 0.1, 0.5, and 0.9. --- # Prior model for `\(\pi\)` You are now a true Bayesian and decide to consult with an expert who knows the specific PhD program well and the following is the prior distribution the expert suggests you use in your analysis. <table> <tr> <th> Π</th> <th> 0.1</th> <th> 0.5</th> <th> 0.9</th> </tr> <tr> <th> f(Π)</th> <th> 0.7</th> <th> 0.2</th> <th> 0.1</th> </tr> </table> The expert thinks that this is quite a hard-to-get-into program. --- # From prior to posterior We have a prior model for `\(\pi\)` that is `\(f(\pi)\)`. In light of observed data `\(x\)` we can update our ideas about `\(\pi\)`. We will call this the posterior model `\(f(\pi|x)\)`. In order to do this update we will need data which we have not observed yet. --- ## Consider data For the two scenarios below fill out the table (twice). For now, it is OK to use your intuition to guesstimate. <table> <tr> <th></th> <th> Π</th> <th> 0.1</th> <th> 0.5</th> <th> 0.9</th> </tr> <tr> <td></td> <td> f(Π)</td> <td> 0.7</td> <td> 0.2</td> <td> 0.1</td> </tr> <tr> <td>Scenario 1</td> <td> f(Π|x)</td> <td> </td> <td> </td> <td> </td> </tr> <tr> <td> Scenario 2</td> <td> f(Π|x)</td> <td> </td> <td> </td> <td> </td> </tr> </table> Scenario 1: What if this program accepted five of the five applicants? Scenario 2: What if this program accepted none of the five applicants? --- ## Intuition vs. Reality Your intuition may not be Bayesian if - you have only relied on the prior model to decide on the posterior model. - you have only relied on the data to decide on the posterior model. Bayesian statistics is a balancing act and we will take both the prior and the data to get to the posterior. Don't worry if your intuition was wrong. As we practice more, you will learn to think like a Bayesian. --- ## Likelihood We do not know `\(\pi\)` but for now let's consider one of the three possibilities for `\(\pi = 0.1\)`. If `\(\pi\)` were 0.1 what is the probability that we would observe 4 of the 5 applicants get admitted to the program? Would you expect this probability to be high or low? Can you calculate an exact value? --- ## Binomial Likelihood Let random variable `\(X\)` be the _number of successes_ (eg: number of accepted applicants) in `\(n\)` _trials_ (eg: applications). Assume that the number of trials is _fixed_, the trials are _independent_, and the _probability of success_ (eg: probability of acceptance) in each trial is `\(\pi\)`. Then the _dependence_ of `\(X\)` on `\(\pi\)` can be modeled by the Binomial model with __parameters__ `\(n\)` and `\(\pi\)`. In mathematical notation: $$X | \pi \sim \text{Bin}(n,\pi) $$ then, the Binomial model is specified by a conditional pmf: `$$f(x|\pi) = {n \choose x} \pi^x (1-\pi)^{n-x} \;\; \text{ for } x \in \{0,1,2,\ldots,n\}$$` --- ## Binomial Likelihood `\(f(x = 4 | \pi = 0.1) = {5 \choose 4} 0.1^40.9^5 = 0.00045\)` or using R ```r dbinom(x = 4, size = 5, prob = 0.1) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.00045 ``` --- ## Binomial Likelihood If `\(\pi\)` were 0.1 what is the probability that we would observe 3 of the 5 applicants get admitted to the program? Would you expect this probability to be high or low? `\(f(x = 3 | \pi = 0.1) = {5 \choose 3} 0.1^30.9^2 = 0.0081\)` or using R ```r dbinom(x = 3, size = 5, prob = 0.1) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.0081 ``` --- ## Binomial Likelihood Rather than doing this one-by-one we can let R consider all different possible observations of x, 0 through 5. ```r dbinom(x = 0:5, size = 5, prob = 0.1) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.59049 0.32805 0.07290 0.00810 0.00045 0.00001 ``` --- ## Probabilities for `\(x_is\)` if `\(\pi = 0.1\)` <img src="slide-1b-event-discrete_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-4-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- ## Other possibilities for `\(\pi\)` <img src="slide-1b-event-discrete_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-5-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- ## We have observed data The admissions of the committee has announced that they have accepted 3 of the 5 applicants. --- ## We have observed data <!-- --> --- ## Likelihood <!-- --> --- ## Likelihood The likelihood function `\(L(\pi|x=3)\)` is the same as the conditional probability mass function `\(f(x|pi)\)` at the observed value `\(x = 3\)`. --- # __pmf vs likelihood__ When `\(\pi\)` is known, the _conditional pmf_ `\(f(\cdot | \pi)\)` allows us to compare the probabilities of `\(x\)` or `\(x'\)` occurring with `\(\pi\)`: `$$f(x|\pi) \; \text{ vs } \; f(x'|\pi) \; .$$` When `\(X=x\)` is known, the _likelihood function_ `\(L(\cdot | x)\)` allows us to compare the relative likelihoods of different scenarios, `\(\pi\)` or `\(\pi'\)`, given that we observed data `\(x\)`: `$$L(\pi|x) \; \text{ vs } \; L(\pi'|x) \; .$$` Thus `\(L(\cdot | x)\)` provides the tool we need to evaluate the relative compatibility of data `\(X=x\)` with variable `\(\pi\)`. --- ## Getting closer to conclusion The expert suggested assigned the highest weight to `\(\pi =0.1\)`. However the data `\(x = 3\)` suggests that `\(\pi = 0.5\)` is more likely. We will continue to consider all the possible values of `\(\pi\)`. Now is a good time to balance the prior and the likelihood. --- ## Bayes' rule `\(\text{posterior} = \frac{\text{prior} \times \text{likelihood}}{\text{marginal probability of data}}\)` --- ## Normalizing constant --- ## Normalizing constant ```r dbinom(x = 3, size = 5, prob = 0.1) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.0081 ``` ```r dbinom(x = 3, size = 5, prob = 0.5) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.3125 ``` ```r dbinom(x = 3, size = 5, prob = 0.9) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.0729 ``` --- ## Normalizing constant Thus `\(f(x = 3) =\)` ```r dbinom(x = 3, size = 5, prob = 0.1) * 0.7 + dbinom(x = 3, size = 5, prob = 0.5) * 0.2 + dbinom(x = 3, size = 5, prob = 0.9) * 0.1 ``` ``` ## [1] 0.07546 ``` --- # Posterior --- ## Posterior shortcut --- ## In summary Every Bayesian analysis consists of three common steps. 1.Construct a __prior model__ for your variable of interest, `\(\pi\)`. A prior model specifies two important pieces of information: the possible values of `\(\pi\)` and the relative prior plausibility of each. 2.Upon observing data `\(X = x\)`, define the __likelihood function__ `\(L(\pi|x)\)`. As a first step, we summarize the dependence of `\(X\)` on `\(\pi\)` via a __conditional pmf__ `\(f(x|\pi)\)`. The likelihood function is then defined by `\(L(\pi|x) = f(x|\pi)\)` and can be used to compare the relative likelihood of different `\(\pi\)` values in light of data `\(X = x\)`. --- ## In summary 3.Build the __posterior model__ of `\(\pi\)` via Bayes' Rule. By Bayes' Rule, the posterior model is constructed by balancing the prior and likelihood: `$$\text{posterior} = \frac{\text{prior} \cdot \text{likelihood}}{\text{normalizing constant}} \propto \text{prior} \cdot \text{likelihood}$$` More technically, `$$f(\pi|x) = \frac{f(\pi)L(\pi|x)}{f(x)} \propto f(\pi)L(\pi|x)$$` --- ## Reminders - Monday quiz - Friday at 5 pm, homework will be assigned. Check course web site. - Before today's discussion, you should have installed R, RStudio, and tidyverse. Even if you have downloaded them in the past, download them again to stay up to date with current versions. Check course web site for instructions. If you are having problems come to my office hours right before the discussion.